When Raiders of the Lost Ark was released in 1981, it was like a jolt of lightning from out of the past. As with George Lucas’ Star Wars before it, here was a throwback to many of the cinematic touchstones high and low that Baby Boomers grew up with: Saturday morning serials, prestige Oscar winners from yesteryear, and even boys’ pulp magazines were sifted through, borrowed from, and recontextualized into one of the most thrilling action-adventure movies anyone had ever seen. Somehow Lucas, who was a producer on the project, director Steven Spielberg, and the whole Indiana Jones team were able to craft a movie simultaneously retro and new.

Of course the younger generations who were swept up in Indy’s adventures may not have noticed any of this. They were here to see Indy outrun a boulder. And as the years have passed, Raiders of the Lost Ark and the whole Indiana Jones trilogy has become its own influential touchstone, passed from one era to the next. But for that very reason, it’s fun to revisit where this now seminal classic in its own right came from 40 years later, and how it’s kept Hollywood traditions alive well into the next century.

The Adventures of Robin Hood (1938)

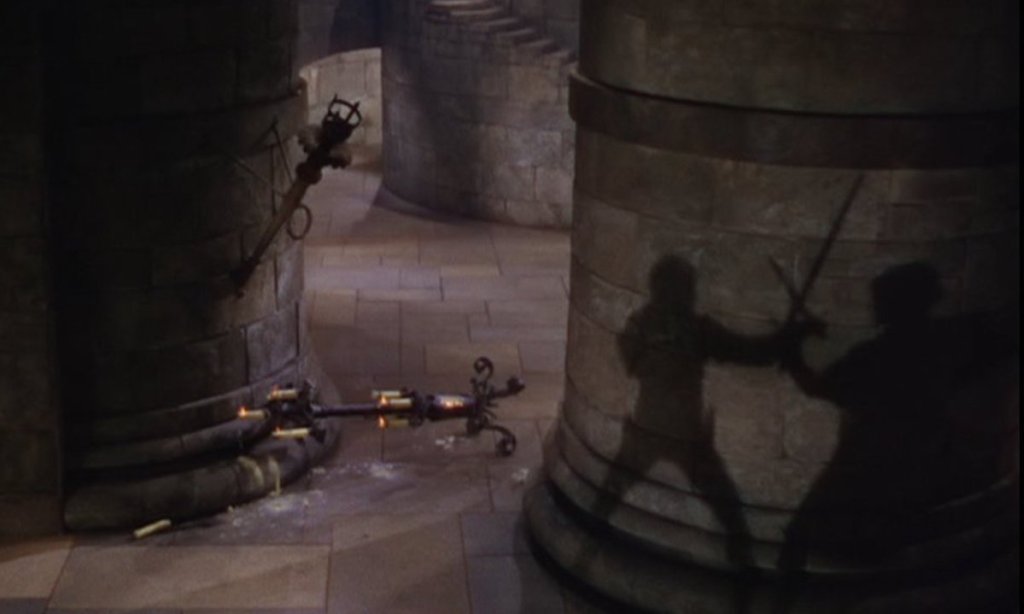

The first of several Michael Curtiz movies that will appear on the list, The Adventures of Robin Hood offers subtle influence on Raiders of the Lost Ark. And you can see it clearly in the scenes set at Marion Ravenwood’s bar in Nepal. First Indy enters the establishment by casting a large, heroic shadow on the wall; the sequence then relies on yet more shadows as the Nazis follow suit, projecting a looming darkness across the room; finally the scene ends with Indiana Jones shooting one of those baddies, and audiences only see the Nazi’s shadow die.

This is all inspired by Curtiz’s famous use of shadowed silhouettes during the climactic sword fight between Errol Flynn and Basil Rathbone in the best Robin Hood movie.

Busby Berkeley Musicals

The musical sequence that opens Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom is centered around the song “Anything Goes,” which was written for Cole Porter’s 1934 stage musical of the same name. It was adapted into a 1936 Paramount Pictures spectacle starring Bing Crosby and Ethel Merman, however the way Spielberg stages the Temple of Doom sequence has more in keeping with 1930s musicals choreographed and/or directed by Busby Berkeley at Warner Bros.

As the filmmaker who pioneered the imagery of dozens of dancers and showgirls forming elaborate geometric patterns and kaleidoscopic shapes, Berkeley relied on complex overhead shots filmed from cranes. Eventually such elaborate staging fell out of favor in lieu of singular song and dance pairings like Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers later in the decade, but in his time Berkeley was responsible for famed dance sequences in 42nd Street (1933), Gold Diggers of 1933 (1933), Gold Diggers of 1935 (1935), Footlight Parade (1933), and Stage Struck (1936). Spielberg obviously wanted to pay homage.

Carole Lombard

Less a direct cinematic influence than a source for characterization, Carole Lombard’s on and off-screen image as a tough-as-nails glamour girl was written into Marion Ravenwood. The character was of course eventually played with her own spark by Karen Allen, but Spielberg and company originally looked toward screwball comedy star Lombard for inspiration during the writing and casting stage. Spielberg even said about Allen that “Karen was the clear favorite because she had spunk and was a firebrand, and she reminded me of ‘30s women. She had that Irene Dunne and Carole Lombard [energy]. She seemed perfect for the part.”

Lombard is a particularly interesting comparison because the ‘30s and ‘40s actor got her start in Hollywood as a starlet who appeared in drawing room dramas, but then carved her path to stardom by playing fast-talking women in Ernst Lubitsch and Howard Hawks comedies, with the latter urging her to carry her own off-screen persona into her characters. Athletic, foul-mouthed, and able to keep up in terms of drink with the men in her life, she brought as much of that into her comedies as censors would allow. Also, perhaps coincidentally, her tragic death in a plane crash drove her husband Clark Gable into World War II with an alleged death wish, which somewhat mirrors a plot point in Raiders of the Lost Ark.

Casablanca (1942)

As yet another Michael Curtiz film, the impact of Casablanca is all over the Indiana Jones movies. A sweeping love story and terrific World War II melodrama filmed during the actual war, Casablanca is generally considered the best movie produced under normal circumstances during Hollywood’s Golden Age. It’s thus an easy touchstone for Spielberg, who emulates many ideas from the picture.

Likely the most noticeable is how both movies communicate international travel while filming on a backlot. Casablanca is not the first movie to show a map onscreen and then draw a moving line across it, which is then juxtaposed alongside international stock footage, but it’s the most famous movie to do so. You can see Casablanca’s influence every time Indy got on a plane, boat, or submarine.

Additionally, much of the relationship between Indy and Marion feels partially inspired by the wounded romance in Casablanca. While, as indicated above, there is not necessarily a lot of Ingrid Bergman’s Ilsa in Marion, Ilsa’s embittered bad blood with Rick (Humphrey Bogart) after a failed relationship is an obvious influence on Indy and Marion. Indeed, Allen’s first line to Ford in Raiders is “Indiana Jones, I always knew you’d come walking back through my door.” It seems a blatant riff on Rick saying, “Of all the gin joints in all the towns in all the world, she walks into mine.”

Gunga Din (1939)

The plot and much of the imagery in Temple of Doom is lifted nearly top to bottom from George Stevens’ Gunga Din, including many of the elements now cited as problematic in both pictures. In Gunga Din, audiences follow Cary Grant, Douglas Fairbanks Jr., and Victor McLaglen as a trio of British officers in 19th century British India. Over the course of the film, Grant’s Sgt. Cutter and his Indian sidekick Gunga Din (Sam Jaffe) discover a secret Thuggee cult, even though the religious order was thought to be extinct. Worse for the colonial powers, the Thuggee intend to expel British rule by following a fanatical, human sacrificing leader (Eduardo Ciannelli) to war.

Read more

Almost all of the second Indy movie’s story about a hidden temple with an Indian cult leader who tortures white heroes comes from Gunga Din, as do several set-pieces and gags. Like Temple of Doom, Grant and Jaffee’s characters struggle with an elephant transporting them through the countryside, and much of the third act pivots around a rope bridge in which Thuggee followers are trapped as the ropes are broken, leaving the fanatics flal to their deaths.

It should be noted Thuggee gangs, which were said to practice ritualistic murder as a part of highway robberies, did probably exist in 17th and 18th century India, although they did not scheme for world domination, nor did they rip hearts from victims’ bodies. Some modern Indian scholars have argued their alleged religious practices were exaggerated or invented by the British authorities who used propaganda while stamping out 18th century gangs.

James Bond Movies

It’s no secret that 007 was a major influence on Indiana Jones. Spielberg originally wanted to make a James Bond movie in the 1970s. After Eon Productions turned him down—so as not to relinquish creative control to the new popular director of Jaws—Lucas pitched his buddy on the concept of what became Indiana Jones.

Elements of Bond still found their way into the Indy movies. Each film is a standalone adventure, and at least three out of four of them follow a rhythmic pattern where after an opening sequence shows the tail-end of Dr. Jones’ previous adventure, we return to his day-to-day life back home. Authority figures then arrive to assign his next quest. Also during all three of the original Indiana Jones movies, Indy had a new love interest from the start.

The influence is so blatant for Spielberg that he came up with the idea of introducing Indiana Jones’ father in Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade… and having him played by Spielberg’s favorite 007, Sean Connery.

King Solomon’s Mines (1950)

Indiana Jones is unquestionably influenced by Alan Quartermain. Whether intentional or not, most fedora-wearing adventurers and great white hunters of western fiction derive from this 1885 literary creation by author Henry Rider Haggard. So the question, then, is which version of Quartermain most directly influenced Spielberg and Lucas? While perhaps the 1937 movie adaptation produced by the Rank Organization (more on them below) was on Lucas’ mind given his nod to the company in Temple of Doom, the most famous iteration of Quartermain’s adventure in King Solomon’s Mines for Baby Boomers comes from a 1950 MGM movie released during Lucas and Spielberg’s youth.

That picture starred Stewart Granger as Quartermain, a white hunter living in what would become South Africa during the 19th century. There his services are requested by an English noble to retrieve his missing brother from the mysterious African interior and to find the legendary mines belonging to biblical figure King Solomon (sound familiar?). The 1950 film made plenty of changes, such as adding a female love interest for Quartermain and reducing the prominence of any black African characters in the already racist Victorian novel to even more primitive stereotypes. It also hasn’t aged particularly well. But it’s probably the closest to a “definitive” cinematic variation on the first adventure novel which created the concept of a “lost civilization” with connections to the Bible, a theme which Indiana Jones would return to time and again.

Lawrence of Arabia (1962)

As the beloved epic from most older Baby Boomers’ childhoods, David Lean’s Lawrence of Arabia is a gargantuan spectacle unlike any other. Filmed in breathtaking 70mm and in the actual deserts traversed by T.E. Lawrence, its visuals are still astonishing 60 years later. Particularly since they really went to those places.

Spielberg attempts to homage that mythical quality repeatedly in the Indiana Jones movies. In Raiders of the Lost Ark, Indy standing tall in the low light of a sunset as workers excavate the Well of Souls visibly emulates the majesty of Peter O’Toole’s Lawrence standing atop a train as men cheer his backlit silhouette. More directly, the final image of Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade is a pure reversal of the most magnificent sunrise you’ve ever seen. In Lawrence of Arabia, Lean captures the sun slowly unfurling over Arabia’s dunes before Lawrence and a companion travel across the sand. In Last Crusade, Indy and multiple companions ride directly into a sunset, which recreates the famous Lawrence of Arabia shot.

The Maltese Falcon (1941)

Arguably the first film noir ever made, The Maltese Falcon made Bogie a star and John Huston an A-list director. It also is a smaller influence on Raiders of the Lost Ark. The Maltese Falcon begins as a murder mystery before giving way to a larger plot in which a sordid collection of gangsters and criminals fight over a MacGuffin called the Maltese Falcon. Alleged to be an ancient, bejeweled prize from antiquity hidden beneath a common-looking facade, men kill and die for it as it’s passed back and forth, a la the Ark of the Covenant.

At the end of the movie, it’s revealed the Maltese Falcon is actually a fake—a forgery made from graphite. While the MacGuffins are a lot more powerful in the Indiana Jones movies, the idea of a magnificent ancient prize driving men mad carries over from The Maltese Falcon, and both Raiders of the Lost Ark and The Last Crusade riff on the reversal, with the Nazis initially finding only dust in the opened ark in Raiders, and the villain of Last Crusade being fooled into thinking the Holy Grail would be made of gold and covered in jewels.

Plus, Peter Lorre’s slimy and giggling depiction of the character Joel Cairo in this movie (as well as several others) appears to be an inspiration for the Nazi played by Ronald Lacey in Raiders.

The Man With No Name Trilogy

Sergio Leone’s seminal Spaghetti Western trilogy—which includes A Fistful of Dollars (1964), For a Few Dollars More (1965), and The Good, the Bad and the Ugly (1966)—were a significant inspiration for Spielberg when he first imagined Indiana Jones’ personality. While there’s more than a hint of Humphrey Bogart to how Harrison Ford plays Indy, there’s also a darker menace, particularly in his first outing. During Spielberg, Lucas, and screenwriter Lawrence Kasdan’s famed story conference for Raiders, the transcripts of which have been saved for posterity, Spielberg name drops a lot of influences for Indy’s personality, including Toshirô Mifune, who starred in multiple Japanese movies directed by Akira Kurosawa. He also mentions Clint Eastwood’s Man with No Name.

Read more

In truth, the Man with No Name is directly inspired by Mifune’s samurai in Yojimbo (1961), but we felt the final allusions in Raiders more overtly leaned toward Leone’s Westernized interpretation of the desperado. You can see it in the first scene when we’re introduced to Indiana Jones through a series of rapidly edited together close-ups of an enemy drawing a pistol, Indy’s whip (as opposed to his own revolver), and finally an extreme close-up of Indy’s eyes, shaded beneath a fedora, as he steps into frame while disarming a foe. It’s Spielberg’s version of countless Leone shootouts starring Eastwood. To further accentuate the influence, Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade is filmed in the same Spanish desert as The Good, the Bad and the Ugly when Indy and his father travel to a fictional Middle Eastern country on their quest.

The Rank Organization Logo

A small nod occurs at the top of Temple of Doom when the Paramount Pictures logo turns into an engraving of a mountain on a Chinese gong that is soon rang in. This is an overt homage to the opening title card of movies produced by the British film studio the Rank Organization, which began with a man also hitting a gong. The studio produced early Hitchcock classics like The Lady Vanishes (1938) and seminal ballet ghost story, The Red Shoes (1948). We imagine Lucas and Spielberg were winking at some of Rank’s pulpier material though, like the first adaptation of King Solomon’s Mines (1937).

Republic Serials During the 1930s-1950s

Admittedly, I’m no expert on the weekly serials that ran in movie houses each Saturday morning during the 1930s, ’40s, and ’50s. However, George Lucas clearly is since they visibly informed Star Wars as much as Indy, what with interstellar adventures like Commander Cody. On the other side of the paradigm there were a cornucopia of mid-20th century Republic serials about adventurers and masked superheroes fighting Nazis that clearly made an impact. One that seems like a specifically heavy influence is Secret Service in Darkest Africa, a Republic serial from 1943 which despite its title is set in a largely lily-white Casablanca (original, ain’t it?).

Over the course of its week-to-week adventures, American secret agent Rex Bennett (Rod Cameron) infiltrates the Third Reich by posing as a Nazi officer in the SS. However, his cover is blown when he goes to Africa to beat the Nazis from discovering an ancient Muslim Tomb which is said to have a scroll that will tell “the Muslims” how to fight in World War II (yep). With incidents like Rex out-swimming German boats to impersonating German personnel, it all has an air of Indy.

Another serial with special consideration is Republic’s Zorro’s Fighting Legion (1939). One of the more popular serials from the FDR years, this classic more than any film I’ve seen likely inspired Lucas for emphasizing Indy’s bullwhip. As with the opening scene of Raiders of the Lost Ark, Zorro uses his whip to disarm foes, swing out windows, and even escape an avalanche. But the stunt that most clearly inspired Indy is a scene where Zorro falls between the horses and under the wheels of a stagecoach, hanging by his trusty fingers. He then catches the back of the carriage and climbs on top to reach the driver’s seat. It’s spectacular, as seen in the above clip, and more or less taken whole cloth for the same stunt from Raiders.

Secret of the Incas (1954)

I’m not sure if Lucas ever publicly spoke about Secret of the Incas, but this Paramount Pictures pulp had a heavy, heavy influence on Raiders of the Lost Ark. Like the Indiana Jones movies, the filmmakers behind it were clearly big fans of The Treasure of Sierra Madre (more below). Also like Indy, they took it in a decidedly more Saturday morning direction. A young Charlton Heston stars in this movie as Harry Steele, a fedora-wearing, leather jacket sporting, adventurer who is after fortune and glory, kid. Fortune and glory. When Harry gets wind that some dastardly archeologists are on a dig down in Peru, having discovered a lost ancient kingdom, Harry gets the bright idea of sneaking onto their dig site and stealing a golden sunburst right out from under them.

Sounds familiar, eh? It’s nowhere near as exciting as Indy, but the basic framework about a gold-seeking cad in a fedora fighting rivals over a buried, priceless MacGuffin is all from here, complete with a love interest who is wooed by Harry’s rival.

She (1887)

This 1887 novel by H. Rider Haggard is considered one of the first and most influential adventure yarns ever written. It’s also an incredibly racist work authored by a Victorian Englishman who spent seven years living in South Africa, making it a prime example of what’s now dubbed “imperialist literature.” Nonetheless, it influenced many other authors, including Rudyard Kipling, J.R.R. Tolkien, Graham Greene, and others who’s work, in turn, influenced Indiana Jones.

She is worth separating from Haggard’s other most popular novel, King Solomon’s Mines, because unlike that story, there was never really a definitive film adaptation of this book. However, Merian C. Cooper of King Kong fame (also an adherent to Haggard’s adventure stories) attempted an Art Deco interpretation of the text in 1935.

In the original story, readers follow the adventures of Horace Holly, the ward of explorer Leo Vincey. Together they discover a lost city in the African interior in which primitive natives worship an immortal white woman whom they refer to as “She Who Must Be Obeyed.” In fact, she is so beautiful that any man becomes her slave after one look into her eyes. Curiously, the Indiana Jones movie which most emulates this is Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull, in which a lost “kingdom” hidden in the Amazonian jungle is protected by primitive natives who worship, if not a white woman goddess, then crystal skulls and the godlike alien beings they belong to. Also if you look into those crystal skulls’ eyes for too long…

The Treasure of Sierra Madre (1948)

Reportedly Huston’s favorite collaboration with Bogie, The Treasure of Sierra Madre is the most influential work on Indiana Jones’ appearance and devil-may-care attitude. This post-war picture stars Bogart as Fred C. Dobbs, a fedora-wearing, hard-drinking, malcontent who becomes obsessed with finding buried treasure. Also prone to wearing a nice weathered leather jacket, Dobbs is a nastier piece of work than Indy. When we meet Dobbs, he’s a drunk with a violent temper. After he and business partners discover gold up on the Sierra Madre mountain, he becomes consumed by greed and ultimately attempts to murder his only friend. He also challenges bandits to a shootout to protect his prize, which eventually results in his death.

Indy never goes so far—which may be why he doesn’t end up getting macheted. But Ford’s visage, as well as the world weary grumpiness he reserves for Belloq or his father, is taken straight from life up on the Sierra Madre.